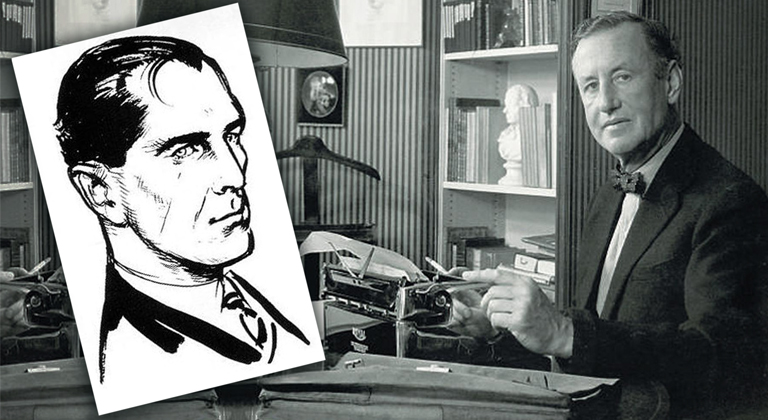

What can Ian Fleming teach us about writing?

I don’t think it’s possible to be a great author without also being an avid reader, first. In fact, while it’s often said that writing daily is the most essential habit an author should develop in order to improve their craft, I think just as important is reading as much and as often as possible. Both of those things are essential ingredients to being a successful storyteller, and there’s no better example of that than Ian Fleming, creator of the iconic character James Bond. There is a lot of benefit in studying authors like Fleming, and as someone who has done just that, Ginger is happy to share what he’s learned.

The 25th James Bond movie, No Time To Die, has hit theaters across the world. Some have hailed it as the “savior of cinema” for finally getting people to return to the movie theater after over a year of pandemic woes. Critics have raved about the movie, even though it’s left some Bond fans gnashing their teeth because of how it ended (no spoilers, though!) Those who loved it, however, really loved it – with Being James Bond reviewer Joe Darlington describing it as a film “Ian Fleming would be proud of.”

That’s an appropriate remark, since the artistry of the author who brought James Bond to life is presented in abundance in this movie. From the style and luxury to the emotion and romance, this is a movie that watches like reading the best works of an admittedly wildly inconsistent writer. For all that some disgruntled fans may argue, No Time To Die is woven from a tapestry of ideas and concepts lifted directly from the books of Ian Fleming.

But why was Ian Fleming such a successful author, and why do the best of the James Bond movies always seem to lean so heavily on the novels Fleming wrote? What is it that makes his writing so effective – and what can we learn from the way he performed his craft?

Ian Fleming as a writer

Ian Fleming’s writing can be categorized two ways. The first is economy – he was a master of short, punchy sentences and wildly evocative adjectives. The reason James Bond books are so eminently quotable is that Ian Fleming said more with a handful of words than some authors could say in a paragraph. James Bond’s fastidious taste was mirrored in the fastidious adjectives and metaphors Fleming used. He’d never use three words when one would suffice, and often used metaphors to hint at a darker subtext. A great example is when Bond was considering resigning from the secret service in Casino Royale, musing: “Everyone has the revolver of resignation in his pocket.”

This stems from his background in journalism. He was editor of his school magazine at Eton, a sub-editor and journalist for Reuters News Agency, and foreign manager for the newsgroup behind The Sunday Times during his life; and the need to convey as much as possible within the tight confines of a newspaper column forced him to develop an acutely keen economy of words very early on in his writing career.

The second way to categorize Ian Fleming’s writing is lurid. Perhaps to our generation – desensitized by Presidents paying off porn stars, and everybody from the babysitter to your bank teller having an OnlyFans account – the original James Bond novels seem tame; but at the time they were viewed as wildly racy, shocking, and naughty!

All of this, of course, added to their appeal! While Paul Johnson of the New Statesman might have dismissed the novel Dr. No as “sex, snobbery, and sadism” it turned out those were just the sort of things people liked reading about, which explains why Fleming sold more than 1.5 million copies within the first four years of release.

The brutal torture scenes, the torrid sex, the grotesque bad guys and henchmen – this all made the books a Grand-Guignol which made reading them feel like a wild, breathless adventure. Fleming’s imagination was breathtaking – but more so was the boldness in which he wrote about things that he knew would shock people.

The irony, of course, is that the things that have led to James Bond’s iconic place in cultural history were the very same things Fleming seemed almost ashamed of in his own life. Badgered by meanspirited reviews, he’d always speak quite self-deprecatingly about his writing – describing the James Bond stories as “pillow books” and “literature with a lower-case l.”

In fact, in a 1957 book review Fleming penned for The Sunday Times, he even complained: “I cannot understand why the great spy novel has never been written.”

Today, in retrospect, we know that he himself wrote that novel – and many others which are also considered the finest of their kind. Part of the reason for their success is how Ian Fleming wrote so effectively and bravely about things which would make people react; and that’s why his books translated so brilliantly into the most-successful movie series of all time.

What can we learn from this?

Ian Fleming’s success as an author has a considerable amount to do with his deft craftsmanship as a writer. While novels like Goldfinger demonstrate that he wasn’t always the strongest at crafting long-form plots (or even coherent ones) the way Ian Fleming wrote captured people’s imaginations and made them feel like they were right there in the moment with Bond – which is why Anthony Burgess hailed the same book as “the best writing he’d seen from Fleming” even though Auric Goldfinger’s wicked scheme falls down like a pack of cards the moment you give it any critical analysis.

Without a doubt, this was because of the concise, journalistic style in which he wrote about even seemingly innocuous details – conveying a grounded sense of ‘being there’ which made readers almost feel like they could taste the luxurious meals they were reading about, or feel the cold steel of a knife pressed against their own throats.

Focusing on conveying as much information and emotion as you can within the fewest number of words is certainly a good habit to get into as a writer. It’s remarkable to look at how short most of Ian Fleming’s novels were when you think about how they made you feel, and the scope of the adventure they took you on.

The other thing I think we can learn from Ian Fleming is not to self-censor yourself too much, and to have the bravery to push certain elements beyond your comfort zone. It would be difficult to imagine James Bond without the lurid sex scenes, graphic torture, or high-stakes thrills – but at the time Ian Fleming was critically mauled for including them.

For all the ways in which writing is a craft, we can turn it into a form of art if we challenge people’s expectations and limitations, and Ian Fleming demonstrates how doing so doesn’t need to be graphic or gratuitous (even if it crosses the line once or twice.)

What was Ian Fleming like as a reader?

When studying any writer, it’s also worth considering what they themselves chose to read; and, fortunately for us, Ian Fleming paid homage to several authors he admired several times in his Bond novels, and provided a long list of books he’d read and reviewed for The Sunday Times.

The fact that he enjoyed contemporary thrillers by authors like Raymond Chandler and Eric Ambler – both mentioned as authors Bond read – reveal one of the eternal truths of being a successful author: Write the kind of books you enjoy.

Raymond Chandler is, of course, the iconic inventor of the ‘hard-boiled private eye’ genre, and Fleming claimed that Chandler had given him advice to “raise my sights” after they’d met for an interview with the BBC one time. From Chandler, Fleming took inspiration to include many of the more lurid elements of his books – but also make the books structurally and narratively more complete.

“[Chandler] seemed to think I had it in me to write proper novels,” Fleming once said of a conversation with Raymond Chandler, “and I was just being lazy about it.”

Eric Ambler is the author of A Coffin for Dimitrios, which Bond was reading in the novel From Russia With Love. Ambler wrote many other iconic novels both before and after that, which are now often given credit for spawning the espionage genre that Ian Fleming is synonymous with today.

In a paper written for The International Journal of James Bond studies, author Lucas Townsend credits Ambler for inspiring Fleming to adopt an “underlying foundation for historically relevant settings, themes, events, and characters.” It was these elements, I believe, which helped project the character of James Bond into the cultural consciousness of the 1950s and 1960s; and he’s remained there ever since.

A brief glance at the many books Fleming reviewed for The Sunday Times also reveals that Fleming very much read within his own chosen genre, or non-fiction books about similar topics such as espionage, crime, and war. Titles he reviewed included The Spy’s Bedside Book, edited by Graham Greene and Hugh Greene, and The F.B.I. Story, by Don Whitehead.

I think this reveals one of the reasons for Fleming’s success within his genre. While many think of Fleming as a pioneer in writing spy adventures, in many ways his gift was paving the trail others had already forged: Distilling down the best elements of his forebears and peers in the thriller business and blending them like a fine Scotch whiskey into what would become the James Bond novels we love today.

What can we learn from Fleming’s reading?

As a writer, there’s no better advice than to read – and Ian Fleming’s choice of reading material proves that.

Like Fleming, you should definitely read books in the same genre in which you write. Without doing so, you’ll be oblivious to the structures, tropes, elements, and style that made those particular books successful; and that ignorance will most likely be reflected in your book sales.

Writing is a craft, not an art, and even the most skilled carpenters and tradesmen always find something new to learn from studying their peers in the industry. Likewise, whichever genre you write in, your own writing will improve when you take the time to read the best of the authors in your category.

Hemingway described writers as “apprentices in a craft where no one ever becomes a master” and that’s something most successful authors would agree with. Ian Fleming’s willingness to embrace and consume the works of other authors helped him learn how to be as successful as he was; and that’s a success which will elude you unless you read as much as you write, just like he did.

But for those of us who love reading, that’s hardly the worst thing in the world to be forced to do, right?

Ian Fleming’s legacy

James Bond has now become one of the most iconic fictional characters in modern history, and it’s all down to the writing of Ian Fleming. His craftsmanship with words and his lurid imagination managed to capture the minds of three generations of Bond fans; and with the release of No Time To Die, many of us have a renewed interest in studying the books from which the movies we love all took inspiration.

Fleming approached writing as a vocation. While he complained to Raymond Chandler that he “didn’t take his books seriously enough” we can see from the way in which he wrote and read that this isn’t entirely true. His background in journalism gave Fleming the editorial discipline to conjure images and emotions with just a few well-chosen words, and all aspiring writers can learn something from that.

Perhaps what we can learn most from Fleming, however, is how he kept on writing despite crippling self-doubt and meanspirited commercial criticism. He once complained: “Writing is an arduous process, you are constantly depressed by the progress of your opus and feel that it is all nonsense and that nobody will be interested.”

All that “nonsense” he wrote about, however, went on to spawn an icon – and right now, at this point in time, everybody in the world is interested in the fictional hero Ian Fleming created. As writers, we can only dream of leaving such a legacy – but even if that eludes us, we can certainly step closer toward it by following Fleming’s example.

Critics rarely get it right. But yet, their voice is so loud it deafens the creative spirit. As the great Martha Graham said to a pal at a cocktail party, “You’ll never see a statue erected of a critic.”

This was such a fantastic article. Thank you!!

In regard to your Fleming piece: One thing Ian Fleming could teach even successful authors about writing is to avoid compelling your reader to re-read a sentence (twice in my case), in an effort to guess what it was that the author actually meant to express. For example, writing “toe the line” when you meant to write “cross the line”. Just saying.

Fixed that, thanks!

Love this post! Couldn’t agree with it more. I’ve never read Ian Fleming, but he’s now on my TBR. I must add, not to spoil the ending, being a lover of romance, the ending of the most recent film did not satisfy. It most definitely left the wheelhouse of the franchise. And, I can’t help but wonder, would Ian Fleming really approve? He could have easily crafted a similar ending to any one of his books…but he chose a brighter path. Would his hero…his powerhouse agent who repeatedly defies all odds and reality…his James Bond…choose this path?