Self-pub or traditional? Which one delivers what an author deserves?

Independent authors still sometimes face a stigma when it comes to their work, whether from the subset of readers that continue to believe a traditionally published book is somehow more “real” or “professional”, or from their own feelings of self-doubt that they hope may be finally quelled by the added legitimacy they’d feel from landing a trad pub contract. But is it really worth it? A decade ago the answer was a clear and obvious yes, but the publishing industry has seen some radical changes since then. To answer whether or not there are any remaining benefits in choosing traditional over self publishing, Ginger digs in to what those big companies still offer, whether it’s worth the cost they demand in return, and what still needs to change.

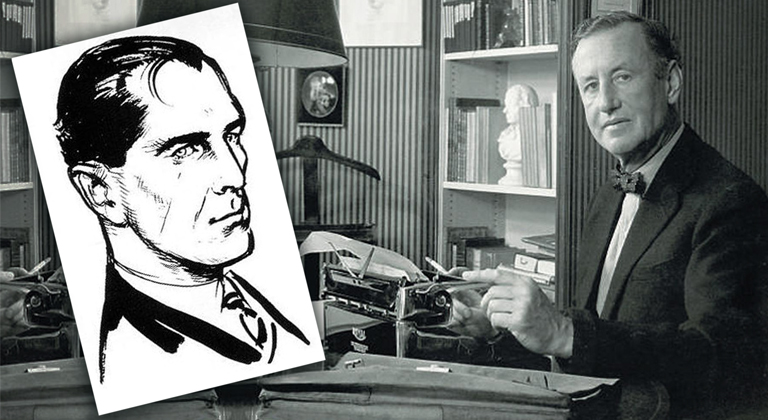

In November, Harper Collins and the Ian Fleming Foundation announced that British author Kim Sherwood had been selected to write the “Double O Trilogy” – three books set in the same fictional world as Ian Fleming’s James Bond, only focusing on other agents who were part of the fabled “Double Oh, Section.”

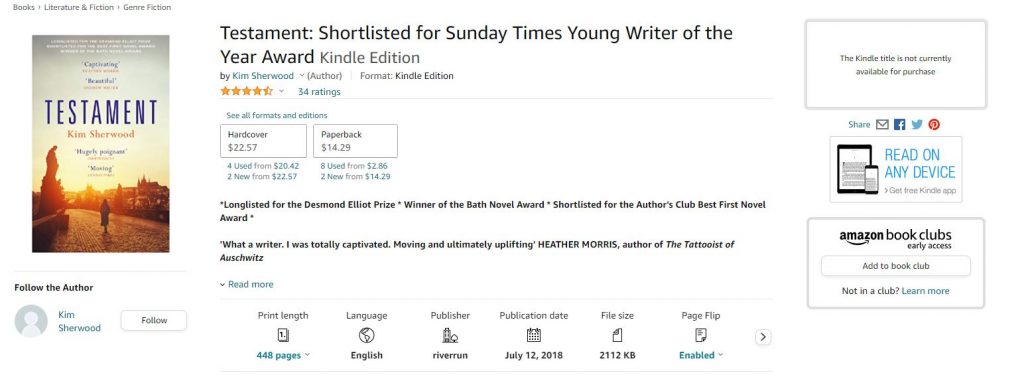

For many, Kim Sherwood was a bold choice. She’d previously only written one book – the critically acclaimed Testament – making her both the youngest and least experienced author to ever pick up a pen in the name of Her Majesty’s Secret Service.

That being said, Testament was longlisted for the Desmond Elliot Prize, chosen as winner of the Bath Novel Award, and shortlisted for the Author’s Club Best First Novel Award. It’s a fearsomely competent debut novel and Kim Sherwood’s writing is noted for her use of metaphors and similes, which were tools Ian Fleming used to great effect in his own books.

So, given the high profile assignment Kim Sherwood is taking the reins of, you’d probably expect the publishers of her debut novel to be preparing to shift serious numbers of her book – after all, her name is trending among all the different James Bond fan communities right now!

In truth, though, it’s the opposite. If you head over to Amazon right now to buy a copy on Kindle, for example, it’s not even available!

Absurdly enough, RiverRun Books – an imprint of Quercus Books – haven’t seemed to have done anything to leverage one of their authors joining perhaps the most famous literary family of all. In fact, she’s not even listed as an author on their website if you navigate through their Author page (although you can find her with the search option.)

To me, this is just another example of how traditional publishers are continuing to fail the authors who provide them with their lifeblood. The pitiful usual royalty rate – 15%, compared to Amazon’s 70% – is bad enough, but it becomes even worse when you witness incompetence like this when it comes to simple things like merely making it possible to buy an author’s book!

And it’s not just limited to smaller independent publishers. Right now, the Justice Department is filing a civil antitrust lawsuit to block Penguin Random House from acquiring its close competitor Simon & Schuster (reducing the ‘big five’ traditional publishers to just four) despite the fact that Simon & Schuster was on the brink of dropping out of the Big 5 way back in 2019 because of their declining sales. Far from creating a monopoly, traditional publishers are being forced to consolidate their operations simply because they’re not capable of growing or expanding unless they do so; and that’s all because of the raw deal they give authors!

But why? Why is traditional publishing plagued with this ungrateful attitude, compounding their financial and practical incompetence? And why do so many authors ignore these problems as they continue to ignore self-publishing and try and get a ‘proper’ publishing deal instead?

The old industry

One of the reasons I believe traditional publishing is dying out is because it stubbornly clings to an outdated business model – like Blockbuster, except with books.

They continue to rely on selling books in brick-and-mortar stores and using editorial reviews and traditional advertising to shift copies – which is woefully inadequate in comparison to the leverage independent authors have through using social media and digital advertising.

I believe this is because traditional publishers were so hesitant in adopting innovations like the Amazon Kindle that it left them way behind the eight ball of digital publishing. They didn’t seem to accept that Amazon and the Kindle totally changed the landscape of traditional publishing. Amazon gave readers an entirely new way to get books – and yet despite the boom in online publishing, the Big 5 and other publishers failed to learn how to adapt to this ‘new normal’ and saw self-published authors come swooping in to take a huge bite out of their lunch.

Book launches, blog tours, social media takeovers, Facebook ads and all the other essential tools of independent publishing are used inconsistently, incorrectly, or simply not at all by many traditional publishers – some of whom have such a poor online presence it suggest nobody there knows how.

But if traditional publishers are so bad at their jobs – why do authors still insist on signing with them?

The new vanity publishing

Back when I was a boy, my mother (also a writer) warned me against ‘vanity publishing.’

These were unscrupulous companies who’d offer to publish your book – but only for a price! And that price would generally be far more than you’d ever make from selling that published book (hence ‘vanity’ publishing – you were paying for the privilege of having a book in print, because that used to mean something back in the day.)

But today, it almost seems like that situation has been reversed. If you’re a self-published author, you’re taking all the risk and responsibility for your book’s success onto your own shoulders by publishing independently, instead of going through a third-party like a publisher. There’s not much ‘vanity’ involved.

Signing up with a traditional publisher, however, provides an author with the one thing even tens of thousands of subsequent sales might not – the prestige of being chosen and represented by a “proper” publisher.

I’ve spoken to many authors who pursued getting “properly” published and they’ve often spoken about it being a badge of honor – a validation that they’re a “real” writer with a “real” book.

It’s fair to say that when it comes to Penguin Random House, or one of the other remaining “Big 5” publishers, that might be a badge of honor worth all the effort. After all, tradpub remains one of the only ways to get physical copies of your book into stores across the country.

Beyond the mainstream publishers, however, I’d argue that many of the authors who they “traditionally” published ended up being disappointed by the results of their “proper” publishing deal. In fact, I’ve seen many of them quit their partnership with this “proper” publisher and go self-published with their second or subsequent books simply because they know they’ll give themselves a much better deal.

In my mind, pursuing a traditional publishing contract has become a new form of “vanity publishing” because authors are sacrificing the financial potential of their work to acquire the “legitimacy” of a traditional publishing contract.

This concerns me – because unlike in the old days, it now costs a publisher very little to make an author’s book available for sale. Print on demand eliminates the need for inventory, but that inventory used to be the reason traditional publishing saw your book in brick-and-mortar bookstores. If the only opportunity to buy an author’s book is on the same digital bookshelves as the work of self-published authors, it reduces the major benefit of “going traditional” to one, simple thing: Getting an email from a faceless, nameless editor telling the author “you’re good enough.”

Why does it continue?

So, why haven’t more authors become clued into this? Well, part of the problem is the fact that self-publishing remains somewhat stigmatized in the eyes of most people. Despite the fact that there are hundreds of authors making a full-time living through self publishing – and selling tons more books than some traditionally published authors – there’s still this attitude of not being legitimate unless you’ve been “chosen” by a publisher.

Another reason is that the true value of the self-published book market isn’t really spoken about, because the majority of self-published titles aren’t even recorded in the “official” publishing sales figures that the mainstream media use (the mainstream media also having a massive stake in the traditional publishing industry.)

So, whenever you see an article like “eBook sales are down” just remember that the article is generally using NPD BookScan or another source of industry data to support their argument – which only includes books with a traditional ISBN that are scanned at the point of sale.

This completely ignores millions of self-published eBooks with nothing but an ASIN, which means the “official” data also fails to record tens or hundreds of millions of book sales – not to mention the royalties generated through subscriptions like Kindle Unlimited.

That’s a bigger figure than you might imagine, too. Books in KU accounted for 14% of all ebook reads on Amazon in 2019, and the ‘Zon subsequently paid authors over $250 billion in royalties as a result. According to these figures, over 85% of all those titles are outside of traditional publishing; meaning NPD BookScan and all those articles citing book sales don’t even mention them.

According to this article, hundreds more self-published authors earn $25,000+ a year than do traditionally published writers, and 40% of the top-selling ebooks on Amazon are self-published – so it’s becoming more and more of an open secret that the best route to successful publishing is to do it yourself!

But the very fact that this sales data is so obfuscated helps maintain traditional publishing’s illusion of legitimacy. There’s still a prestige to being “traditionally” published that people just can’t seem to get past, and people not being able to clearly compare earnings and book sales between traditional and self-published authors is perpetuating that.

It’s also allowing traditional publishers to get away with representing their authors poorly, or even not at all. Looping this back to the beginning of my blog post: After news of her being picked as the new James Bond author become public, how many people went looking for a copy of Testament by Kim Sherwood? I know I did!

But how many of us were left disappointed when it wasn’t available! How many hundreds or thousands of sales of her book has Kim missed out on simply because her “traditional” publisher didn’t have their act together?

I think enough is enough. I think writers have missed out on too much for too long – and today, they’re often being exploited by traditional publishers. It’s about time more people knew about this, and perhaps it’s about time somebody did something.

So, what’s the solution?

But when I say “do something” what does that something look like?

Obviously, it wouldn’t be right to regulate publishers as private businesses, and it’s not like we’d be able to anyway – but I think the publishing industry is long overdue for some cooperation towards understanding the industry we all work in.

Here are my suggestions for things that could be done differently:

Standardize Sales Data Across Platforms

Currently, Amazon and other independent bookselling platforms don’t officially publish sales data in the same way the traditional publishing industry does through things like NPD BookScan. While I’m sure the ‘Zon has its own reasons for not wanting to share that data (perhaps weakening their position in negotiating with the “Big 5” publishers) I think it’s fair for the thousands of authors who publish through their Kindle Direct Publishing platform to have some form of transparency into how many books really get sold there.

An Author’s “Bill of Rights”

Now that self-publishing is an entirely valid alternative to a traditional publishing contract, I think it’s time traditional publishers were held accountable in what they provide for an author who’ll be giving them 55% more in royalties they might otherwise have earned on self-publishing on Amazon. It’s not that 15% of royalties is too low (although it is, and I’ll get to that), it’s just an author deserves to know they’re getting something of value in return.

For me, these are pretty standard requirements – simply making an author’s book available for purchase! In the case of Kim Sherwood, for example, RiverRun Books hadn’t made the Kindle version of her book available in the US (despite it being available in the UK) and therefore potentially cost her hundreds or even thousands of ebook sales when the huge news about her being selected to write the Double O Trilogy was announced.

I think certain requirements like a high-quality proof and edit of the manuscript, a paperback version through Print on Demand, plus a quality cover for both ebook and paperback versions should be the very bare minimum that traditional publishers offer authors, too – and while I think that’s setting a very low bar, it’s very disappointing when you hear about the occasional traditional publisher still failing to reach it.

An Increase in the Royalty Rates

For over a century, royalty rates for a traditional publishing contract have been around 15% – which was pretty fair when you considered that publishers used to have to gamble on investing in hundreds or even thousands of printed books before they themselves could make any profit.

But digital publishing changed that – yet for many authors, the royalty rates remained the same. Now, the traditional publisher can potentially make so much more profit, since they’re not reliant on selling physical books alone; and yet none of that profit is being passed on to the author.

One of the reasons Amazon instantly attracted so many authors to self-publish was because they offered a 70% royalty rate on digital books priced between $2.99 and $9.99 and that instantly made more sense to authors who already knew what they were doing to market their books, or were willing to learn.

So, given that, I think it’s now time for authors to consider standardizing a higher royalty rate for authors. It doesn’t need to be astronomically higher – but it does need to offset the higher margins in digital publishing, just as the editing and marketing services a traditional publisher should (hopefully) offer will ideally justify taking their cut of the royalties.

Traditional publishing doesn’t need to die – it needs to change

All that being said, traditional publishing isn’t and shouldn’t disappear any time soon. As much as I’ve complained above, there are things of enormous value that traditional publishers offer authors, and there’s still a lot of sense to be made for why many authors still want to have a “real” publishing deal.

When it comes to the “Big 5” publishers, it’s an undeniable fact that the only way you’ll ever see your paperbacks in bookstores across the country is if you go through them. The complexities of the print business, the stock model of bookstores, and the huge risk involved in printing books in sufficient quantity to make them profitable has left only the biggest juggernauts in a position to routinely stock the shelves of Barnes and Noble and Borders. Currently, this is a marketplace that self-published authors can’t seem to make any real headway in conquering.

Likewise, there’s a huge appeal to having a publisher “take care of everything.” If you get a traditional publishing contract, you sign it with the expectation of quality editing, successful marketing, and all the other elements that are difficult for a self-published author to master on their own. To many, losing that additional 55% of their potential royalties is worth it just for the comfort of getting to pass the hard work off to people who know what they’re doing.

It’s just I think traditional publishers should start thinking about moving towards more of a service industry than merely a sales one. Obviously, they want to make as much profit as possible, leveraging the creativity of their authors – but given how profitable self-publishing can be, it’s now entirely justified for authors to expect competent marketing of their book in return. I think publishers should consider themselves in competition for the best authors – and actively promote what services they’ll provide for that author (like social media, website presences, blog tours and the like) in return for signing with them.

It’s a radical shift to how things have traditionally always been, I’m not going to lie. Authors used to think they were lucky to get a traditional publishing contract.

Now, it’s publishers who are lucky if they can sign a potentially successful author – and this change in the power dynamic should be reflected in the professionalism with which traditional publishers try to achieve success for their authors.

By realizing that traditional publishing and self publishing all have their places in the publishing industry, we’ll be able to offer more for authors and deliver a better experience for readers. Ultimately, that’s going to be better for everybody.