The Book Marketing Trio You Need to Succeed

When it comes to sending out queries or even publishing, there are three challenging forms of book marketing copy that authors need to master. All three are essential, though they each serve a different purpose, but what they have in common is that they need to be compelling and to the point, without any wasted words, in order to capture the interest of their intended audiences as quickly as possible.

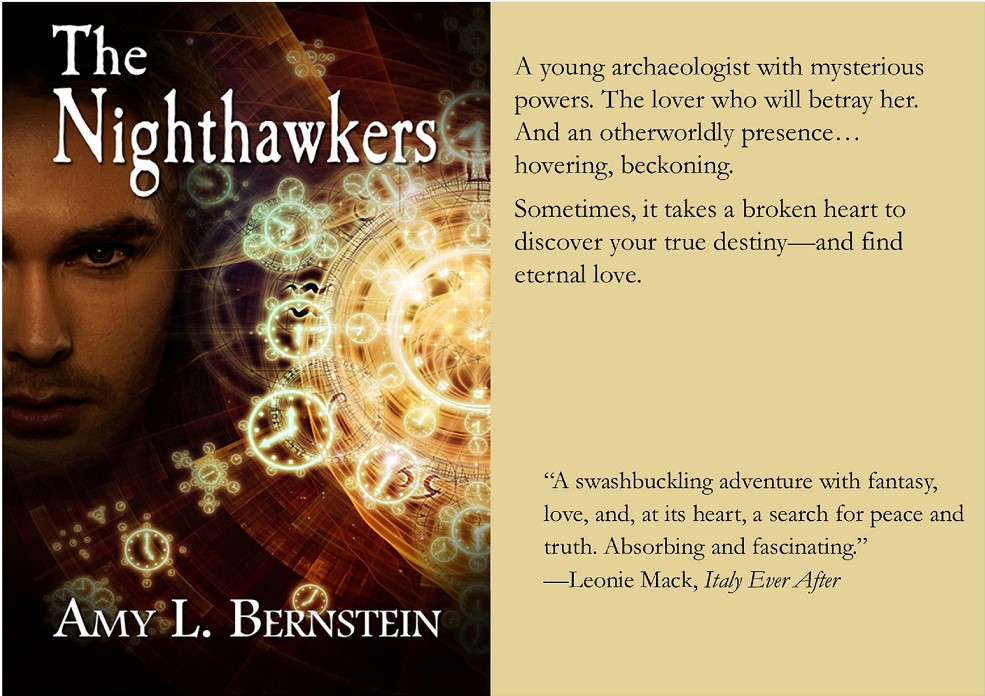

Author Amy Bernstein has plenty of experience writing all three forms, and is here today to help explain when and where to use each one, as well as tips and best practices on writing them in the first place.

A Logline, Synopsis, and Flap Copy meet up at a writers’ conference (or a bar, if you’re in that mood). The Logline utters two sentences, then shuts up. The Synopsis blabs on and on indiscreetly, and the Flap Copy gets everyone’s attention with some short, pithy observations.

These guys each have their own personality. And, yeah, they’re an acquired taste. But after hanging out with them awhile, they kind of grow on you. Little by little, you come to depend on them—each of them—and you learn to appreciate their quirks.

Seriously, all but the most pampered authors today need to befriend the Logline, Synopsis, and Flap Copy. You won’t get too far in publishing (or querying) without these trusty companions by your side.

So let’s get acquainted, shall we?

The Logline: Sell the sizzle

The logline grew up in Hollywood’s film industry, but it’s been adopted by the book world. You may hear it called a teaser, a pitch, or a hook (craft purists will argue these are all different, but let’s not quibble over semantics). Whatever you call it, you need a logline to grab a micro-second of an agent’s, publisher’s, or producer’s attention, and even, in some cases, a reader’s.

The bad news about loglines is they are notoriously difficult to write well, especially if you’re an author close to your own work. The good news is there are formulas you can tap into to guide their construction.

A good logline is an elevator pitch on steroids—powerful and able to deliver a quick knock-out punch. Author and screenwriter Jeff Lyons defines the logline as “the narrative essence of your story that conveys the high concept, the tone, and core emotion of your premise, and does all this in one short sentence (or two).”

If that sounds easy, you’re not doing it right. It isn’t easy. Formulas help tame the beast. One of the best known formulas is distilled as the KilligatorTM method put forth by British author Graeme Shimmin. It goes like this:

In a (SETTING) a (PROTAGONIST) has a (PROBLEM) caused by (an ANTAGONIST) and (faces CONFLICT) as they try to (achieve a GOAL).

Here’s the formula in practice, with constituent parts identified in brackets:

The British Secret Service [SETTING] asks a retired spymaster [PROTAGONIST] to find a Soviet mole [PROBLEM] who must be one of his former protégés [ANTAGONIST]. He can trust no one [CONFLICT] as he tries to discover who the traitor is [GOAL]. (Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy by John le Carré)

I suggest you begin with this approach and see where it takes you. You may learn a lot about your novel—its structure and story arcs—along the way. Consider that a bonus of logline research.

But before gouging out your eyeballs, you might also try a formula that’s logline-light. Boil it all down to one sentence that highlights the protagonist, conflict, and goal. Here are a couple of examples, courtesy of writer and blogger Erica Verrillo:

An unwilling wife who despises her roguish husband eventually comes to adore him. (Taming of the Shrew by William Shakespeare).

A young FBI cadet must confide in a manipulative convicted killer to receive his help on catching another serial killer who skins his victims. (Silence of the Lambs by Thomas Harris).

Both methods work well in summarizing the stakes in a high-concept format that captures—nay, demands—attention. If you can’t shoehorn your novel into one of these formulas, you might ask yourself some hard questions about whether you’ve constructed your book properly. Because virtually every work of fiction can bend to the will of the logline.

A few details to notice about loglines:

- Don’t name characters; it’s unnecessary, as these examples prove.

- Don’t straightforwardly summarize the plot (that’s the synopsis’s job); focus on the story’s overarching concept.

- And choose the most powerful adjectives you can; make every word count.

Once you’ve crafted a compelling logline, use it to open your query letter to agents. It’s a sure-fire way to grab attention and encourage them to read at least a few sentences more. Use the logline on social media when you’re promoting your book. It’s tailor-made for Twitter and Instagram. And use it on book-related graphics. That’s exactly what I’ve done here for my novel coming out in June. Note that I don’t really tell you what the book’s about, but I do try to interest you in its stakes:

The Synopsis: Spill the beans

Writers complain that writing a synopsis of their novel is harder than writing the novel in the first place. I maintain it’s easier than writing the shorter logline—but still not a cakewalk. Synopses generally come in three forms: very short (one meaty single-spaced paragraph); short (two double-spaced paragraphs) and long (at least one full double-spaced page, about 250 words). It’s increasingly rare to encounter a gatekeeper who wants more than a page-length synopsis, and often, in an emailed query pitch, one of the shorter versions is sufficient. You should have versions of all three on hand to meet the varying demands of agents and publishers.

The purpose of the synopsis, regardless of length, is to offer a clear, energetic summary of the entire book, including how it ends. This is not the place for cliffhangers or rhetorical questions (Will she survive?). Some agents will skim the thing and then focus on the end, in particular. Then they may loop back to see how you got there.

In general, you want to hit the primary beats of your story—the major story arcs, in other words. Include key plot twists, milestones, and revelations. Name the major characters (they have shed the anonymity of the logline) and secondary characters who advance the story. You can omit the great-grandmother who appears in one scene and doesn’t move the plot along.

There’s a handy Master Class on writing a synopsis that offers excellent guidance. For example, write your synopsis in the third person, regardless of your book’s point of view. Be sure to “reveal it all,” as the Master Class summary puts it. And choose your tone wisely: write in a style that alludes to the tone and mood of the book itself. If your book is humorous, make the synopsis light and funny. If you’ve written a hard-boiled detective novel, capture that snarky edge.

A badly written synopsis merely reports “this happened, then this happened, then that happened.” Boring! Done poorly, it’s overloaded with details that don’t help you tell the story. The principles of the logline still apply: focus on character, conflicts, and goals.

Here’s the synopsis for Pride and Prejudice and Zombies. Since it’s a film, this reads like a long-ish logline, but qualifies as a short synopsis that works equally well for a book:

In the 19th century, a mysterious plague turns the English countryside into a war zone. No one is safe as the dead come back to life to terrorize the land. Fate leads Elizabeth Bennet, a master of martial arts and weaponry, to join forces with Mr. Darcy, a handsome but arrogant gentleman. Elizabeth can’t stand Darcy, but respects his skills as a zombie killer. Casting aside their personal differences, they unite on the blood-soaked battlefield to save their country.

Note that the setting, problem, and conflict are explained out of the gate (drawing the reader in immediately), followed by the introduction of the protagonist (Elizabeth) and antagonist (Darcy), and the stakes they must confront. And we know how it ends: they will save the country. In a longer version, you might relay some details about the ups and downs of the battle, add a line or two as to how they save the country, and say something about the story’s romance.

You’ll find that the shorter versions of your synopsis come in handy a lot, not only when pitching to agents via email or the common template known as QueryManager, but also when engaging with publicists, podcasters, bloggers, and others who need to know a bit more than the logline reveals.

The Flap Copy: Leave ‘em wanting more

This is the copy written on the back of your paperback book (aka jacket copy). On the hardcover version, it’s often on the inside front flap of the dust jacket. (Hence the origin of the term, when most books were published between hard covers.) This is also the text that appears on Amazon’s page for the book (and other e-tailers).

If the logline is like smelling the sizzle of a cooking steak, and the synopsis is eating a few bites of that steak, then flap copy is watching the chef season and prepare the steak, whetting your appetite for the main course, uh, the book.

Many indie publishers ask their authors to write their own flap copy. But in reality, this is usually a collaborative effort between author and publisher (meaning, your assigned editor). This little bit of real estate is too important to leave to chance since, like the logline, it functions as external communication with potential readers and reviewers.

No pressure or anything, but market studies have shown that flap copy is the second most important factor leading to a book purchase, after favorite author. This is where you really want to hook the reader—to capture the imagination while also holding back. Flap copy is a seduction. It’s a difficult balancing act that requires extremely artful wordsmithing.

I would argue that flap copy comes in two parts—one mandatory, one optional. The mandatory part conveys the shape of the story without a single extraneous detail. Here’s that paragraph for The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett, a recent bestseller:

The Vignes twin sisters will always be identical. But after growing up together in a small, southern black community and running away at age sixteen, it’s not just the shape of their daily lives that is different as adults, it’s everything: their families, their communities, their racial identities. Many years later, one sister lives with her black daughter in the same southern town she once tried to escape. The other secretly passes for white, and her white husband knows nothing of her past. Still, even separated by so many miles and just as many lies, the fates of the twins remain intertwined. What will happen to the next generation, when their own daughters’ storylines intersect?

A few observations about this flap copy. It reads like a short synopsis—except the ending is withheld. That’s because we’re in seduction mode here. If you tell me the ending, why should I read the book?

Also note that we’re given a surname, and no other names. They would only take away from the high-stakes tale itself. And every line in this flap copy advances the story, whether by giving us a glimpse of the story’s setting or the challenges and conflicts the main characters must overcome. Remove one single sentence, and the sense of the whole falls apart. We also have a sense of the genre, which is key; this is literary fiction centered on an African-American experience.

The second part of flap copy, which is not always included, is the editorial comment at the end: a quoted review or praise statement about the book. The Vanishing Half supplements its core jacket info with a glowing appraisal of the book as “riveting,” a “brilliant exploration,” and an “engrossing page turner.”

If you’ve got it, flaunt it. If not, then make an airtight case for your story as a fascinating tale, well told, with high stakes that leave the reader wanting to know more.

The best way to learn to write flap copy is to read versions of it on scores of different books, from comedy to romance to horror. Study how those paragraphs are structured. What comes first? What’s last? How does the text excite your interest?

I used to think that writing a novel would be the hardest thing I’d ever do. Until I met my friends the Logline, Synopsis, and Flap Copy. They taught me that when the last line of my book is written, then the real work begins.