Hollywood Could Learn from Romance Novels About Strong Female Characters

Hollywood is desperate for ‘strong female characters’ – but romance/adventure author Simone Scarlet believes they’re looking in the wrong place for them. Here is her argument to Hollywood that they would be better served by mining romance novels for examples of strong female characters than continuing to write ‘shared cinematic universes’ using the same tired tropes that haven’t worked for years. She even ends the post with a few book recommendations of where they can start looking!

Warning, this post contains some a spoiler or two about Captain Marvel.

The other week, I went to the cinema to watch Avengers: Endgame, which came off the back of Captain Marvel. I’ll have to admit – I loved them both, especially the inaugural outing for Marvel’s newest superhero.

With Captain Marvel, it was great to see the 1990s brought to life again, to watch Samuel L. Jackson as I remembered him from Pulp Fiction and other 90s movies (thanks, digital technology) and I thought Carol Danvers – “Captain Marvel” herself – was pretty cool. I’ll admit, I choked up towards the end of the movie, where there was a flashback scene of all the times Carol had been knocked down, but got back up again – as a little girl, a teenager, and then a military recruit. There’s no way any girl who’s struggled to be taken seriously can fail to be moved by that scene.

But that being said, I didn’t go into the movie completely without expectations. There’d been a lot of publicity about Captain Marvel centering on how ‘fanboys’ were upset with the movie, and how it was being touted as ‘feminist’ and one of the ‘first superhero movies to have a female lead’.

Now, I’m kind of a nerd, and my Spidey-senses tingled when I started to read headlines like that; because I knew they weren’t even remotely true.

I mean, obviously Wonder Woman from the year before disproves that this was the ‘first’ female-led superhero movie – and you could also argue that last year’s Atomic Blonde was in a similar vein. In fact, the idea that Captain Marvel was one of the ‘first’ action movies to be headed up by a female lead doesn’t really hold water when you look at a lot of other movies and movie franchises, like the Alien movies (with the lead being Ellen Ripley) the Hunger Games series, the six Underworld movies, three Tomb Raider movies, the six Resident Evil movies (with lead character Alice) Kill Bill Parts 1 & 2, Angelina Jolie in Salt, the Charlie’s Angels movies and my favorite, 1990’s La Femme Nikita, which was remade in 1993 as The Point of No Return.

That’s not to argue that there’s any equality in terms of female and male-led movies. There have been 25 James Bond movies, for example, and there’s never any shortage of action movies with big, muscular men front-and-center on the posters. It’s also worth noting that a lot of these female-led movies have very sexualized leading ladies; or scenes that objectified them heavily.

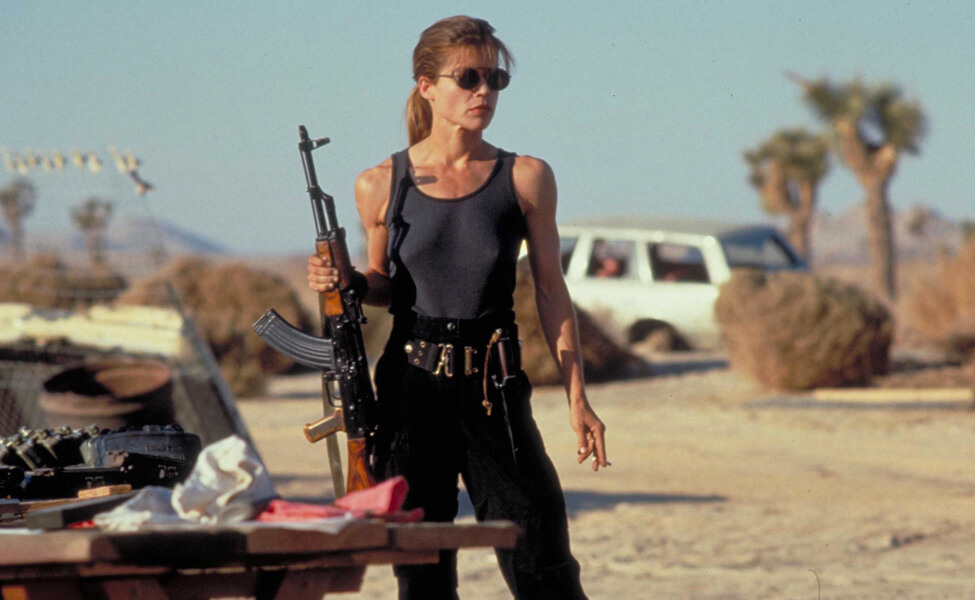

But that being said, the more the concept of ‘strong female characters’ is touted by Hollywood and the media, the less it rings true for me. I look at older movies and older female characters – like Ellen Ripley from the Aliens saga, or Sarah Conner from Terminator – and something really stands out to me:

Those female characters were better.

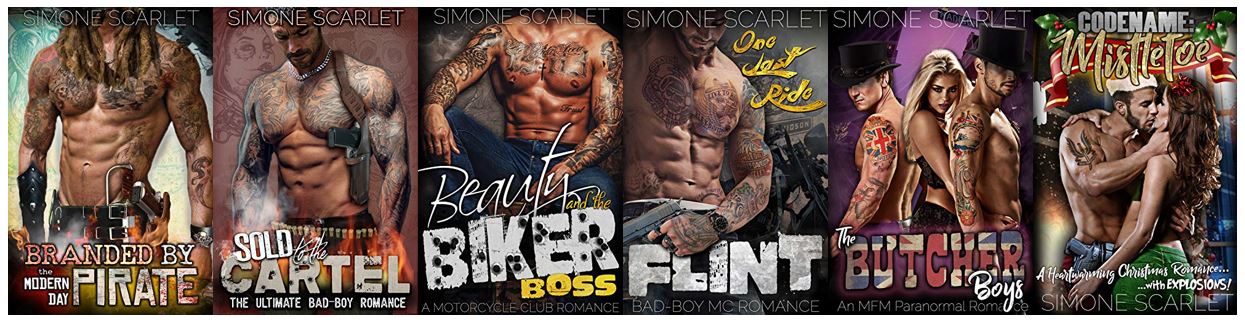

Just all around, the female characters who led movies and movie franchises before it became a ‘thing’ to celebrate female-led movies were just better written, more interesting, and more convincing; and I think that’s something we need to address. As the author of romance books that mirror some of the tropes of Hollywood – in fact, this year’s Christmas book Codename: Mistletoe was basically a romance-novel homage to Die Hard – I think that Hollywood could look to the romance genre for a lot of inspiration about what it means for a female character to be ‘strong.’

What is ‘strength’?

To me, the moment that I noticed movies getting the concept of a ‘strong’ female character wrong was in 2001’s Shrek (bear with me here!) In that movie, the ogre Shrek has to rescue ‘damsel in distress’ Princess Fiona, and on the way home they run into a version of Robin Hood (the famous English folk hero, who has a mysteriously French accent in this iteration.) Shrek obviously thinks he’s going to have to ‘rescue’ Fiona all over again – until it turns out that she is a butt-kicking karate machine who sends Robin Hood and his Merry Men fleeing for Sherwood Forest.

It’s an entertaining scene and obviously helps establish that Fiona is a girl who can look after herself – but from a characterization standpoint, it makes no sense at all.

(I know, I know, I’m picking holes in a movie that features a talking donkey, but I do have a point to this example.)

Fiona was a princess, and she’d spent the last decade locked up in a tower. Exactly when and how did she learn karate? To the degree that she could beat up an entire gang of trained bandits?

Obviously, it made no sense at all – and this is Shrek, so maybe we shouldn’t think too hard about this! But, at the same time, it’s clear the scriptwriters were told ‘make her strong’ and they just decided to magically give Fiona world-class martial arts skills even though it made absolutely no narrative sense whatsoever.

In more modern movies, I think the one that irked me a little was the character of Rey in Star Wars: The Force Awakens, who was just a regular girl living on a junkyard planet… Who managed to expertly fly the Millennium Falcon after jumping behind the controls just seconds earlier, and defeat prodigiously powerful dark-Jedi Kylo Ren in light-saber combat even though she’d never had any formal training in how to use a light-saber. Even Luke Skywalker was trained (briefly) by Yoda in The Empire Strikes Back – and to reiterate how inexperienced he was, he got his hand cut off within minutes of confronting Darth Vader.

There’s a real problem when you try to make characters ‘strong’ by giving them abilities and talents that don’t really gel with the origin or backstory of that character. It seems like a really lazy way to make a character ‘strong’ and it’s one of the reasons why so many of these disgruntled fanboys get their knickers in a twist about characters like Rey being a ‘Mary Sue’ – which is a term nerds like me use for a female character who is unrealistically lacking in flaws or weaknesses.

While I really enjoyed Captain Marvel, to a certain extent I felt like that about the character of Carol Danvers, too. She was a fiercely-determined, prodigiously-talented Air Force pilot, whose ‘character development’ led her to become a fiercely-determined, incredibly-powered super-heroine who could defeat an entire fleet of orbiting warships seemingly without breaking a sweat.

That thread continued in Avengers: Endgame, and my 10-year-old son and I discussed how (spoiler alert) if Captain Marvel had turned up an hour earlier, it would have been a really short movie.

That’s why I put Carol’s ‘character development’ in quotes – because in some ways she had no character development. Now, don’t get me wrong – I still liked her character a lot, and I’m excited about seeing her in the next phase of Marvel movies… But she’s not a good ‘character’ because her ‘strength’ comes externally, rather than from within.

Real ‘strength’

In terms of Hollywood movies, some of the best ‘strong’ female character development I can remember comes from the first two Terminator movies. In those films, the heroine – Sarah Connor – goes through two massive and very different developmental arcs in each movie.

In the first movie, she starts off as a regular Los Angeles waitress, and a robot from the future comes back to the 1980s to try and kill her. In the beginning of the film, she’s a total damsel in distress – needing to be rescued by handsome hunk Kyle Reese. By the end of the film, though, he’s taught her to administer a combat dressing, load a shotgun and make homemade explosives. She ends up ‘terminating’ the killer robot, and becomes a legitimate bad-ass in her own right.

In the second movie, Sarah is that same kick-ass heroine – except she’s gone so far down the rabbit hole of paranoia and militarization that the authorities have locked her in an asylum and taken her child from her. Her developmental arc in this movie is to rediscover her humanity – first by sparing the life of Miles Dyson, who ‘invented’ the computer system that took over the world, and then by reconnecting with her estranged son.

In the second movie especially, Sarah is the strongest of ‘strong, female characters’ because she can shoot guns, make explosives, beat people up and generally kick butt – and it all has a legitimate narrative origin (she didn’t magically learn these skills like Fiona did in Shrek, or Rey did in Star Wars: The Force Awakens.) But it’s also demonstrated that ‘strength’ isn’t just the ability to blow stuff up. It’s humanity, humility and mercy that makes her ‘strong’ and (it’s almost like this was the theme of the movie) separates humanity from the machines that are trying to eradicate them.

To me, this has always served as a good template for what makes a ‘strong’ female character – and because my stories tend to take place in an action/adventure environment, I’m all about strong female characters.

In fact, when I’m plotting out romance novels, the first thing I focus on is always the female protagonist. This is because I write my stories from first-person perspective, alternating between the hero and the heroine. The female character is the one I’m obviously going to relate to most-strongly, and basically experience the story through. My readers are mostly female, and I imagine they feel the same way. I want them to like my heroine, and also be able to relate to her.

Relateability doesn’t come from strength. Quite the opposite, in fact. I don’t think anybody would argue that it’s the flaws in characters that they relate to most – and what makes them fall in love with them is watching the characters overcome or face these flaws (as we all wish we could do with our own.)

I don’t need to explain that the most essential rule to storytelling is for the main characters to experience development throughout their tale – to emerge at the end of the story a different (ideally stronger) person than they were when they began it. This is, to my mind, where the ‘strength’ comes from; and what was lacking in tales like Captain Marvel, where Carol Danvers was pretty much the same gritty, determined bad-ass from the beginning of the adventure to the end of it; except she could also shoot magical plasma blasts, or whatever, by the final scene.

I am certainly the least-qualified person to tell you what ‘should’ be the basis for a good romance heroine, but I can tell you what works for me: I like to imagine my heroine, and place her in an environment, in which she could experience her entire story without the male lead.

I know, I know – for a romance author this might sound counter-intuitive; but I’ll explain my justification. It’s something I call the ‘reverse James Bond.’ In the old James Bond movies – and, don’t get me wrong, I’m a fan of them – there are a lot of times in which you could lift the love interest out of the movie entirely and it would play out pretty much the same. Goldfinger might be an exception, but in movies like The Man with the Golden Gun and Goldeneye, the female characters are largely just set-dressing – there to establish that James Bond is heterosexual and not much more – and even the more modern Daniel Craig movies like Quantum of Solace experience the same issue (tell me, Bond fan or not, can you even name the female love-interest in Quantum of Solace?)

I mean, let’s get real – there was no love interest in Skyfall, one of the most recent Bond movies. In fact, the ‘Bond girl’ was probably Dame Judi Dench, in the role of Bond’s boss, M.

I like to base my books on the flip-side of that – the female protagonists face an insurmountable obstacle that exists outside of their male love interest. The most important element of the book to me is the love story between my leading lady and leading man – but I want my leading lady to be fully-realized, and have an origin and motivation and purpose that exists outside of the male character.For example, in my novel Branded by the Modern-Day Pirate, my heroine Miranda wanted to avenge her father, and kill the man who drove him to suicide. She happens to meet up with a sexy modern-day pirate who wants to do the same thing – but if she’d missed out on encountering Racio at all, she’d still have continued on her original mission.

I mentioned Codename: Mistletoe earlier, and even though that’s a story which was deliberately written as a homage to Die Hard, at the heart of it is a female protagonist – a down-on-her-luck student called Holly who is trying to cover her rent by spending a night as an exotic dancer. It just so happens she took a shift at a corporate party that gets invaded by terrorists. Now, don’t get me wrong – sexy ex-serviceman Dex is a really useful ally to make (not to mention a sexy one) but even if he wasn’t in the story at all, Holly would have been in the same predicament, and would have fought just as hard to get out of it.

Obviously the love story – and the sex – is at the core of each of my books; but I don’t want to write about women who are helpless, who don’t have a motivation and purpose of their own, and who only find themselves in jeopardy because of their love interest. Even in my two more popular books, Sold to the Cartel and Breaking the Double Agent, the heroines might begin as prisoners of the misunderstood love interest; but they got there pursuing goals that had nothing to do with them originally.

Likewise, if my heroines have butt-kicking skills, like martial arts expert Charlie from Jackal & Rawhide, or gun-toting secret agent Tatania from The Butcher Boys, my goal is for them to be seen as having developed these talents organically, as part of their character’s history, and they make sense in relation to the story.

More importantly, the characters who don’t have these butt-kicking skills are still smart, useful and strong. In Sold to the Cartel, my heroine Valerie might not be a gun-toting, butt-kicking martial artist – but she’s got an eidetic memory and is a world-class financial whiz. Miranda from Branded by the Modern-Day Pirate might not be a khuki-wielding, skull-crushing beast like her love interest; but she was raised by a merchant seaman and can plot a navigational course, repair a ship on the high-seas, and – most importantly – resist cruel and menacing torture at the hands of her enemies.

What’s love got to do with it?

Having said all this, you might be asking – okay, so where’s the romance? And I’m getting to that.

Obviously, as a romance writer, the love and sex is at the core of my story; but that’s where I want the escapism, passion and excitement to be. When I craft the heroes of my tales, they’re generally externally ‘strong’ – to the degree that we romance authors love. Whether it’s Racio the pirate, Mendoza the cartel boss, or Coyle the badass biker boss, they’re all – to a certain extent – impossibly ‘strong’ and powerful. Most of my heroes stand more than six and a half feet tall, have physiques like The Rock, and can crack heads, break bones and cause mayhem like the best action movie hero. This is, for me, what I like to write and read about. In real life, sensitive, nerdy men might be attractive – but when I read steamy fiction, I like to lose myself in the fantasy of monstrous men with foot-long cocks and hands the size of dinner-plates (just perfect for curling around a heroine’s slender throat. Rawwwrrr!)

You can judge me for that if you want – but I write fantasy, so I own it.

But what I will say is that for all the external strength my characters have, they’re all ‘weaker’ than my heroines. That’s the whole point of them. They’re men who mask their flaws with an external demonstration of ‘strength’ and the moment they meet my female leads, they find the one person in the world who can ‘fix’ them. My heroes have eyes only for the heroine – it’s as if all other women suddenly become invisible – and they’ll do anything they can to protect, cherish and (yes) bed their love interest.

There are definite escapist aspects to these love affairs – in Branded by the Modern-Day Pirate, there’s Miranda getting whisked away on Racio’s pirate ship, The Tempest, or Izzie straddling the back of Coyle’s Harley Davidson in Beauty and the Biker Boss. My female leads get whisked away by their dashing hero, are given countless orgasms in sweaty trysts with them, and have these men drop to their knees to give their undying declarations of love…

…but it’s the men who are the ‘damsels in distress’ in my stories, and it’s the women who ‘rescue’ them and help them overcome their challenges and flaws. My female leads have challenges and flaws of their own to overcome – but they rescue themselves; or at least I like to think they do.

I mean, I have no authority to say that this is the ‘right’ way to write a romance novel, but it’s the technique I use; and I like to think it makes me much more enthusiastic about writing from my heroine’s perspective, and much more eager to experience the hero’s development and healing. I think to a certain extent I’m as guilty of any other genre writer for engaging the trope of a woman ‘fixing’ a man (like the ‘manic pixie dream girl’ in male-oriented romantic comedies) but the difference is that my heroes are devoted to my heroines, whereas my heroines can do-very-well-on-their-own-thank-you-very-much.

How does all this fit with the Hollywood problem?

So, I’m pretty sure I was trying to make a point earlier, but I got distracted with all this talk of bulging muscles and foot-long… nevermind.

My point – and I’m certainly not trying to say I’m the authority on this subject – is that Hollywood should look to a genre like romance because it contains countless books with amazing examples of what a real ‘strong, female character’ is like. I like to think my books are fast-paced, entertaining and fun – but they’re certainly far from the only or best examples of amazing female characters who manage to be ‘strong’ and yet have relatable flaws and challenges, and undergo some serious character development along the way.

Given how Hollywood created some fantastic ‘strong’ female characters in the 1980s and 1990s – before ‘strong female characters’ were a tickbox movie producers tried to check – I think it’s time to return to the drawing board and look at what ‘strength’ really is; and because it’s such a female-focused genre, romance is a great place to start with that.

In terms of old-school Hollywood, some great examples were Ellen Ripley in Aliens – who gets taught by Corporal Dwayne Hicks (played by Michael Biehn, who coincidentally played Kyle Reese, who we’ve already discussed teaching Sarah Connor everything she knew in the original Terminator) to use an M41A Pulse Rifle. This explains why she’s able to reap through an army of alien xenomorphs at the climax of the movie (instead of magically knowing how to use this military tech, in the same way Rey was able to magically use a lightsaber in The Force Awakens.)

I’m also kind of fond of Pussy Galore in the old Bond movie Goldfinger, who led a squadron of all-female pirates, could go fist-to-fist with James Bond in a fight, and was addressed as an absolute equal by the villainous (and titular) Goldfinger. She was a fearsomely strong female character before ‘strong female characters’ were even a thing!

The character of Valeria in Conan the Barbarian was also a legitimate bad-ass, and Red Sonya in the movie of the same name boasted that she’d never ‘lay with a man’ who couldn’t defeat her in combat (and as far as I remember, love-interest Arnold Schwarzenegger still hadn’t managed to do that by the end of the movie.)

I think what made these female characters so compelling and ‘strong’ is that there was a narrative reason for their strength, and they were well-written characters – and they weren’t perfect!

Modern day ‘strong female characters’ like Rey from Star Wars and Carol Danvers from Captain Marvel are just too… good. It’s almost as if the scriptwriters are worried that giving these characters flaws makes them ‘weaker’ and we live in such a hyper-sensitive, politically-correct environment that any conscious decision to make a female character ‘weak’ might be viewed as sexist. But as a writer, I feel that the whole definition of ‘strength’ isn’t the ability to kick butt, it’s the power to overcome your weaknesses. In fact, I’d go as far to say that the entire reason Hollywood gets this so wrong right now is because (and I’m going to write this in bold) you cannot have strength unless it originates in weakness.

And the irony is that this goes for male characters as much as female characters – and just as Hollywood gets female characters more and more wrong (by removing everything that makes them a ‘character’) we’re going through a period in which male characters are stronger, better-written and more relatable than ever – because they’re deliberately written to be ‘weak.’ Just look at the chauvinistic Don Draper from Mad Men, or Walter White from Breaking Bad. They’re not ‘good’ people, and they have serious – possibly even irreconcilable flaws – but there is a goodness and humanity even in their weakness, and that’s why they’ve become such cultural icons and people love them.

In the world of Marvel movies, it’s the same thing. Tony Stark is an arrogant, self-entitled ass – but that makes his journey of maturity and sacrifice so much more compelling. Thor starts off as a swaggering jock, but gets brought so low that when he finally builds himself back up in Thor: Ragnarok and Avengers: Infinity War he’s stronger than ever.

Because our society is so terrified of presenting women as ‘weak’ we’ve now got characters like Captain Marvel who don’t have the origin in weakness to be able to develop their ‘strength’ and become what the scriptwriters are so desperate for – strong, female characters.

I recommend those scriptwriters pick up a romance novel or two – because I think a much-maligned genre is where they might find the inspiration to create really dynamic, relatable female characters…

…and Hollywood – you’re in luck. I’ve got some recommendations for you!

Recommended Reading

As a romance writer, I read voraciously – and in recent months here are some titles that I feel have some really powerful, strong and relatable female leads.

McMillan File by CB Samet

McMillan File by CB Samet

Mica McMillian is the ultimate ‘strong’ female character. She’s a scrappy, savvy private detective who has an addiction to danger and a passion for justice. This is the third book in The Rider Files series, but the first one I read – and I absolutely fell in love with Mica. She’s tough, determined and also achingly human.

The great thing, though, is that Mica is just one of the strong women you’ll meet in CB Samet’s series. The Rider Files in question focus on a protection agency run by Maxine Rider, who features in all the stories, and she’s almost like Judi Dench’s ‘M’ from the James Bond series, except tougher, more capable and even sexier. What I loved about this book is how Maxine identified how strong and talented Mica was, and by the end of the book was actively trying to support this sassy young badass (and allowed her to date Maxine’s son.) Even better than books about strong female characters are books in which strong women support each other – and CB Samet has that down to an art.

Mated to the Alien Warriors by Corin Cain

Mated to the Alien Warriors by Corin Cain

All of Corin Cain’s Aurelian Empire books are awesome – fast-paced, incredible steamy and featuring towering alien warriors who are yearning desperately to share one, true love (yes, four-way love scenes abound!) My personal favorite is Mated to the Alien Warriors, because it has an incredible heroine in Inspector Sandra Bellinks, who is assigned to track down the monster responsible for committing a mass genocide. She’s reluctantly forced to accept three alien detectives on this assignment – and as they track down a sinister cult and try to stop one man’s reign of terror, Sandra has to face the question of whether to embrace her growing attraction to these three sexy aliens, or focus on the career she’s spent a lifetime trying to build.

Sandra is – as you’d expect of a space-age police inspector – completely kickass, but in a way that makes strong narrative sense. The conflict she faces – deciding which path to follow in her love and career – is achingly relatable and will keep you guessing to the final page. For me, though, the kicker is the individual development each of our three sexy aliens go through; as Sandra helps them overcome their own internal conflicts and emerge stronger as a result.

Swear to Me by Lilian Monroe

Swear to Me by Lilian Monroe

I discussed earlier how ‘strength’ doesn’t need to involve kicking ass or shooting guns – and that’s what I loved about Mara McCoy, the heroine of Swear to Me. The second in the Clarke Brother’s Series, this book follows Mara as she returns to the small Adirondack town she grew up in – to face the dissolution of her marriage, the tyranny of her mother, and mending the rift that has kept two of the town’s foremost families feuding for a generation.

Lilian paints a vivid picture of the gorgeous small-town setting, and her leading man – Dominic – is deliciously strong, sexy, yet in need of healing. Rather than with her fists or space-aged lasers, like in my previous two recommendations, our heroine solves her challenges with strength of moral purpose, bravery and love. It’s a truly heart-warming read and you’ll fall in love not just with Dominic and Mara, but the whole town the series is set in.

The Final Word

So, Hollywood – if you want to option any of the recommendations above (or, hey, any of my books) just say the word. In the meantime, remember the golden rule about all characters – ‘strong female characters’ or not:

The need to be human.

They need to be flawed.

They need to be broken.

They need to have a purpose and a past – and it’s only by conquering their internal challenges that they can overcome the external ones.

This is something that’s been missing from too many recent movies – even the awesome and entertaining Captain Marvel – and until Hollywood gets to grips with it, we’re going to have more fanboys griping about ‘feminist’ movies and the worst, and most unforgivable thing, is that they might have the tiniest sliver of a point.

Hollywood – you can do better: and the romance genre can show you the way. Get busy.

Simone, I completely agree with you. Wonder Woman was mild fun, but bored me, because well…she was perfect. No real arc, no character development. She was super tough and pretty much awesome to begin with, so where’s the story? Same problem with Marvel. Now Sarah Connor, I LOVE her character. Imagine they had begun with Terminator 2 and Sarah was already buff, crazy and utterly awesome, it simply wouldn’t have had the emotional resonance from beat down, heart broken woman, to tough, unshakeable mother. But in today’s climate, it’s hard to write hidden toughness, or weak to strong leads, because many readers (not just Hollywood writers) expect insta-heroes. They critique women’s roles who are products of their times or lives and have acquired magic or fighting skills through some kind of download not linked with their personal growth. In fact, writing about any flawed characters, especially flawed women is a tough sell.